December 8, 2006 - January 19, 2007

Fairy tales and the fantastical characters that populate them reveal much about the cultures that produce them. While rich in fantasy and wonder, traditional fairy tales present a simple moral world-view; good vanquishes evil and lives happily ever after. These feel good scenarios provide hope and solace in the unnerving world today, inspiring artistic retreats into fantasy, imagination and the carefree innocence of childhood. However, in a contemporary moment defined by conflict and complexity, when the reductive logic of "good versus evil" has been used to launch unjust imperial wars and compromise constitutional rights and civil liberties, the straightforward narrative and the fairy tale ending must be questioned. The artists in this exhibition respond to both these prerogatives by manipulating a fairy-tale cast of personal icons derived from fantasy, dreams and pop culture to mine the fractures and fissures of contemporary life.

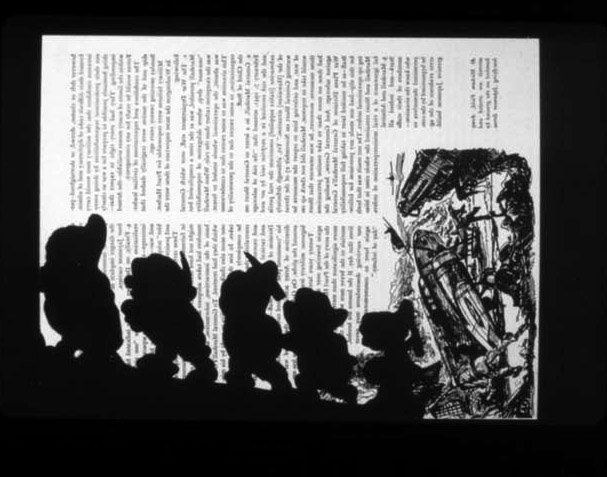

The stars of Jon Cuyson's multi-layered paintings, drawings and collages are the many favorites of Disney's All-American cartoon pantheon. These familiar childhood friends are transformed into multivalent symbols that simultaneously serve as icons of the unrelenting global spread of American culture and register traces of the lingering trauma, on all sides, of America's many colonial adventures, both past and present. In Death March (2005), a troupe of dwarfs is emptied of color and deployed as a silhouette, on the page of an old history book. The title refers to the forced transfer of thousands of Filipino and American POWs out of the Bataan Peninsula in the Philippines by the Japanese in 1942, an event marred by unimaginable acts of cruelty. The silhouette ensures the cartoon image's legibility while simultaneously providing a pictorial void, encouraging the projection of the viewer's histories, fantasies, nightmares and desires. The silhouette, a formal absent presence (or vice versa), serves as a powerful metaphor for the liminal existence of a new immigrant. Text, pattern, cartoon characters and media images of the military are scattered across the seven panels of Someday My Prince Will Come (2006), a recent work that reveals the artist's growing interest in text and language. Juxtaposed with the media images, the fairy tale title reads as a hollow plea for magical salvation, increasingly the tenor of the current war in Iraq. The adjusted phonetic spellings capture the pronunciation and cadence of a Filipino accent adding a further complexity to our interpretation of both text and image.

Harnessing fabric's emotive and communicative power, Jan Ru Wan uses found clothing and textile to create complex, but delicate, sculptural installations that use a concise formal lexicon to tell rich stories. Widely traveled, Wan draws on a variety of different Asian cultures in her work. The Chinese title of the work in this exhibition consists of a pair of linguistic equations that reveal the reductive association of woman with marriage and home in traditional Asian culture; the character for "marry" is a literal fusion of those for "woman" and "home". The sculptural installation is a pithy physical representation of this equation; a cluster of delicate origami houses sits atop an inverted, second-hand kimono, its rectangular sleeves carefully arranged flat on the ground to providing a formal entry into the piece. The cheap, used kimono, registers the actual lived history of an individual woman and its palette of reds and yellows resonates through the work, each house formed by the careful folding and ironing of a piece of dyed fabric; a silk ribbon cascades off each architectural form, representing an individual wish. The piece as a whole oscillates between the individual and the universal, the repetition of individual elements creating a merged collectivity.

For many immigrants assimilation is a process fraught with anxiety and guilt as the culture of origin, both voluntarily and involuntarily, fades. Saeri Kiritani counters this experience through a broad multi-media project that reasserts her cultural identity through a literal and symbolic re-immersion in rice, a key cultural signifier of Japan and an integral part of everyday life there. The use of rice is inspired, as traditional cuisine is often one the strongest ties that immigrants have to their cultures of origin. In addition, "ethnic" cuisine is an integral part America's multicultural landscape and for many Americans their first taste of another culture is literally through taste. In 100 Pounds of Rice (2004), the self is literally and symbolically reconstituted out of rice; using Elmer's glue and rice, and translucent rice noodles as hair, Kiritani recreates her likeness as a "rice woman," a fantastic Super-Japanese alter ego. Rice (2003) recreates this dramatic transformation in real time; the artist's face and body are gradually covered with a second skin of rice, eventually blending into the white background. The conflicted relationship immigrants have with such cultural signifiers, which are both familiar and comforting but also serve as markers of difference and components of stereotypes, is evoked by the sculptural self-portrait's pedestal, a mountain of rice, that the figure both triumphantly emerges out of or drowns into.

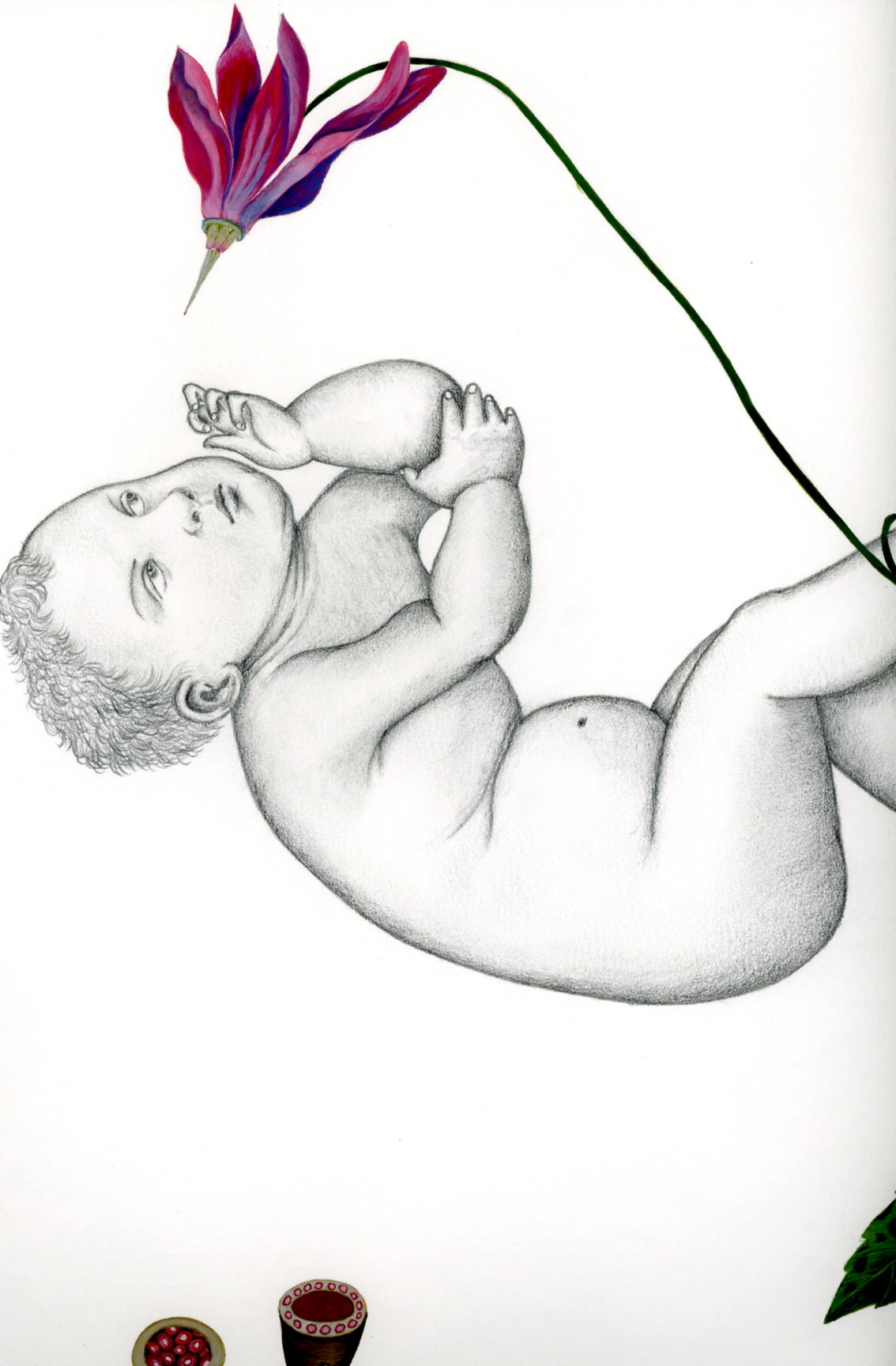

Naoe Suzuki's precise, psychologically charged drawings, executed in graphite and mineral pigments, appropriate imagery from the history of art, medical catalogues and plant life. The human, vegetable and medical are brought together in constellations that simultaneously suggest and resist narrative and allude to contemporary anxieties about biotechnology, modern medicine and the human body. These fantastic visual combinations are echoed in the wonderfully irreverent titles of the works - Pseudopiggybackemia splenium (2004), Erythrosatyrium (2004), Compulsive ancylojunction (2004), etc. - each a Mysterious Syndrome 'diagnosed' by the artist, scrambling modern medicine's latin lexicon to create a series of kooky pseudo-illnesses. By disrupting this lexical register the drawings mock the conventions of modern medicine - a body of knowledge that gains much of its power and authority from its limited access - and express a profound suspicion of the quick fix panaceas it promises, a noble pursuit often compromised by the pharmaceutical industry's quest for profit. The human protagonist of each drawing is a swaddled baby Jesus drawn from a Renaissance painting and the ambiguous visual encounters between religious and medical imagery hint at present debates about stem cell research, cloning and intelligent design. These cool, clinical drawings are paranoid prognostications of our imminent hybrid future when biotechnological innovations may finally transgress the traditional limits of the human.

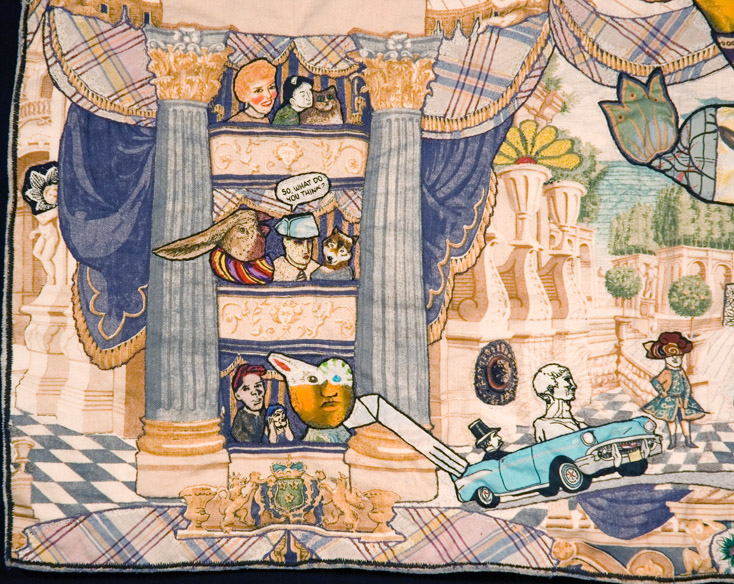

Fusing together scavenged scraps of commercially made fabrics onto differently patterned grounds, China Marks creates playful and fantastic, if often disturbing, tableaus, populated by grotesque figures reminiscent of both Renaissance painter Giuseppe Arcimboldo's vegetal composites and Dadaist Hannah Hoch's collages. Wielding an industrial sewing machine as a graphic tool the artist skillfully uses its trademark zig-zag stitch to draw, blend, shade and model, transforming jumbles of patterns, textures, and forms into what she calls "sewn drawings." Compositions are not pre-determined and reveal themselves during the laborious drawing process as narratives emerge intuitively in response to the imagery and patterns in the scraps used. Marks's cartoon-like figures reveal her long-standing interest in manga and anime and she sources her fabrics accordingly; in Behold the Messenger Raw and Cooked (2006) a samurai hairpiece tops a striding figure whose left thigh is an inverted blue and white Chinese porcelain vase. Simultaneously, her patchwork aesthetic links these works to America's strong folk art tradition of quilting and to its more recent feminist reappropriations. Both reflecting and refracting these various cultural references, Marks's labor-intensive works serve as emblems of a multicultural America, literally stitching together a variety of disparate images, techniques, and cultures.

While the works in this exhibition manipulate and transform the fantastical and imaginative worlds of fairy tales to convey darker truths they also reveal a common formal or aesthetic strategy, that of visual fracture. Either through a collage aesthetic or a fragmentation or dispersal of a unified form, the artists in this exhibition use both subject matter and formal technique to reflect on the conflicted, fractured experience of being Asian in America.

-Murtaza Vali, Guest Writer

Murtaza Vali is an art historian, critic and curator based in New York

Naoe Suzuki

Naoe Suzuki

Undodgerolid meatus

Mineral pigment and graphite on paper

2004

Saeri Kiritani

Saeri Kiritani

Rice Installation

DVD

2006

Jan Ru-Wan

Jan Ru-Wan

Woman+Home=Marry/Woman=Marry-Home

Dyed and printed images on non-woven materials, printed mirror and kimono

2005

Jon Cuyson

Jon Cuyson

Death March

Acrylic on history bookpage

2006

China Marks

China Marks

Christ Enters Left

Fabric, lace, thread, plastic netting, silk-screen ink, fusible adhesive

2006