BRIEF HISTORY OF BASEMENT WORKSHOP

- Eleanor Yung, co-founder

Revised November 2024

1969 Chinatown Study

It was in 1969, or maybe 1968, that I experienced firsthand, helicopters hovering closely overhead, and the smell of tear gas permeating over the Student Union at the University of California, Berkeley. I then saw student protestors, running away from campus police and the smoke-filled air, piling into the adjacent Shattuck Avenue. I hurriedly stepped further away from all the commotion and unrest. My brother Danny had just left two years prior for the east coast, and I was still immersed in the Berkeley campus riots, students fighting for Third World Studies and the famed People’s Park. Those were formative years for many people, inspiring, exciting and memorable, the ‘60s, the decade marked by the civil rights movement.

After graduating with a sociology degree, I followed both of my brothers’ footsteps and came to the east coast. As soon as I arrived, Danny put me to task as part of a nine-member team of his Chinatown Study Group. This was during the tail end of the 1969 Chinatown Study1, his Master’s thesis in Urban Planning at Columbia University, the first-ever research study on New York Chinatown’s urban landscape and its demographics. Chinatown at that time was a mysterious and unknown place to most people. It was just a few blocks of an enclave of an inner city bounded by language barriers, cultural differences, and racial discrimination and exclusion.

After the passing of the Immigration and Nationality Act of 19652 which lifted quotas for Chinese immigrants, a large influx of them moved to San Francisco and New York’s Chinatowns, mostly to join and reunite with their families. This inevitably created more crowded living conditions and resulted in multiple complex problems. The Chinatown Study Report found that any one apartment could be housing numerous families, and some buildings had one shared bathroom in the hallway for different apartments.

With a team of eight other graduate students3, Danny mobilized fifty bilingual college students to go door-to-door interviewing Chinatown residents, and another twenty-five graduate students to conduct building surveys and make site evaluations. The Chinatown Study provided much clarity on the living conditions and hardships of residents, and how they had to struggle to sustain their livelihood and survive in the United States. It was completed and published at the same time as the 1970 Census data collection, which at that time identified people as Black, White, or Others. Asian (Asian American) was not yet a category.

In Spring 1970, I got a call from Danny to meet him at the basement of 54 Elizabeth Street. As I walked down the stairs into the basement, there he was standing in the center of the room, beaming, his arms outstretched, motioning the space to me, asking excitedly, “What do you think!?”

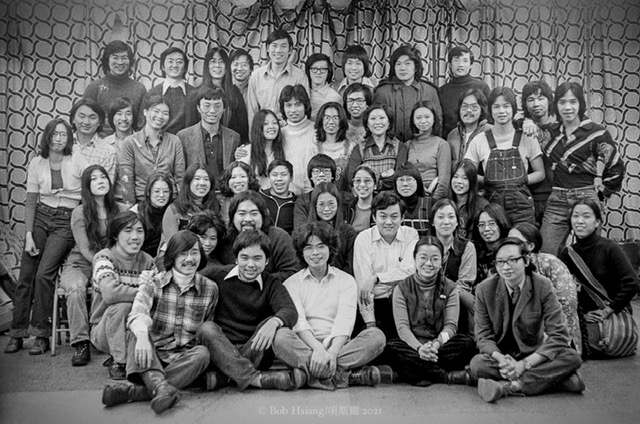

Danny believed that materials we gathered from the community should remain in the community, and that accurate data would serve as the basis for relevant and necessary programs and actions. That spring, he rented the basement space for a two-year lease, to do just that and much more. The physical space was used not only to store materials, but also became a place where many people would gather, particularly college students and young people. For the student recruits of the Chinatown Study and their friends, it became a hub, a hangout place in Chinatown. “Let’s go eat in Chinatown... I’ll meet you at the Basement,” became an often-heard phrase. Started by mostly foreign-born graduate students and many undergraduate Chinese Americans, Basement Workshop quickly expanded to include others, and the term ‘Asian American’ was easily and appropriately adopted.

All Ideas and Discourses Were Welcome, and Nothing was Impossible

Danny welcomed people to join Basement Workshop, and invited them to participate in its activities. He encouraged them to create their own projects, and often made suggestions and provided space for their ideas. There were no hindrance or obstacles for new projects to begin. The creative energy of that time generated dynamic interactions and activities. The space provided at the basement of 54 Elizabeth Street was not only a physical place, but also a creative space. Basement Workshop was like a blank canvas where all ideas and discourses were welcome, and nothing was impossible.

In late 1970, Basement Workshop was incorporated and registered with New York State as a non-profit organization, and, in 1971, received the tax exempt status from the IRS.4 With this status, funds could be raised to enable its many budding projects. Activities ranged from programs for the immediate Chinatown community and network building across the nation to raise the awareness of ‘Asian America', to concerns of national issues, for example, the Vietnam war. It was a significant period when Asian American activism was growing.

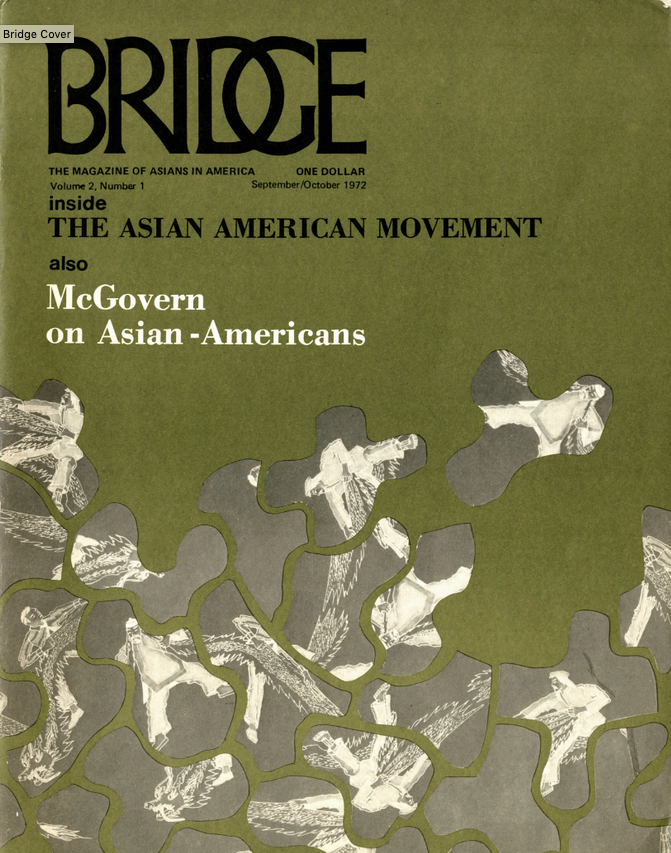

Danny categorized the activities and programs in the early ‘70s into four areas, although distinctive yet often overlapping. The first of these was the publication of Bridge, a quarterly magazine and a tool to raise national awareness and for networking.

Building Bridges

The concept of a magazine that could speak to the Asian American population began before Basement Workshop. In the late ‘60s, friends who were faculty members and graduate students of Columbia University and The City University of New York (CUNY) met to discuss the issues concerning Chinese Americans.5 The idea of a collection of materials and news, to be disseminated to various places in the country, was borne at that time.

Bridge: the Magazine of Asians in America began its publication by Basement Workshop in 1971. The magazine was a means to enhance communication amongst communities, primarily academia. By developing a national network, Bridge not only could disseminate information, but also help facilitate activities concerning Asian American students, faculties and departments.6

With an Editorial Board of Asian American journalists spearheaded by Frank Ching and Danny Yung,7 Bridge covered national and international topics pertaining to Asian Americans, including news, politics, academia and research, communities and the Asian American movement, sex and gender issues, as well as arts and culture, supplemented with art, photography, illustrations, and comics.

An example of a timely issue of Bridge (v02_n01) was the 1972 presidential election, which surveyed politicians for their responses to Asian American concerns. In this same issue were articles on “The Emergence of the Asian American Movement” by Paul Wong, and “A Day at the Mural” by Bill Wong that covered mural works by artists Tomie Arai, Alan Okada and many others.

Bridge reached major colleges and universities, connecting professors, teaching staff, and students in these institutions. To raise awareness and advocate for the formation of Asian American Studies Departments in colleges and universities, and to raise funds for the magazine and for the other programs at Basement, we made trips to Washington D.C. lobbying for support from legislators. Today, complete issues of Bridge have been archived in university libraries, and the W.O.W. Project in NY Chinatown has completed the digitization of all the issues of Bridge.

Community Activism

While efforts were being made on a national level in building bridges and creating Asian American networks, at home in Chinatown, the Chinatown Community Planning Workshop provided services to Chinatown, and engaged in the debate on ideology and politics in relations to the organization, the community and Asian America in general. Hands-on programs included direct services to Chinatown residents both young and old. This educational, arts, and social service programming at one time served more than 200 individuals, offering classes and workshops: Chinese language for the American-born Chinese and English for non-English speaking immigrants, Big Brother Big Sisters and tutorial programs for the youngsters, Children Arts Projects in the public library and parks, and tax services and citizenship classes for those who were in urgent sometimes desperate needs8. Among those involved was Chuck Lee, the graphic designer for Bridge and a English as a Second Language teacher to garment workers, who became one of the primary organizers of the annual Asian Pacific American Heritage Festival coordinated by the Coalition of Asian Pacific Americans (CAPA)9.

Classes for the community were held at an additional space at 1 East Broadway, home to Michio Kaku, now a prominent physicist and professor at The City College of New York/CUNY. His home was heavily used both as a classroom, and as a meeting place for political and ideological discussions.

Constant heated discourses on ideologies and politics, and on the appropriate direction for the organization and the community, splintered Basement Workshop members to form or join other groups, including but not limited to the Workers’ Viewpoint, I Wor Kuen (IWK), Chinese Progressive Association (CPA), and Asian American for Equal Employment (AAFEE). Many members engaged and extended their activities to include labor and employment demonstrations10, in health and healthcare11, safety issues and concerns, and local small business and tourism issues. Young people coming through Basement Workshop filtered into these other community activities. Chinatown was robust with energy and action.

At Basement Workshop, Takashi (Robert) Yanagida (1948-2021), the then-executive director, advocated political relevance for the organization.

Research and Information: The Foundation of Organizations and Activism

The Asian American Resource Center started as the storehouse of the raw data collected from interviews and subsequent analysis of the 1969 Chinatown Study. Under the care of Rocky Chin, then a Law student, the Resource Center library continued to grow with newspaper and magazine articles, research and academic papers, as well as audio and visual documentations, all related to Asian America. In 1972, Basement received a seed grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities to conduct an Oral History Project. Danny recruited Fay Chew Matsuda (1949-2020), then a student of Social Work, to take charge of this project interviewing community seniors. An article on the Oral History Project written by Odoric Wou can be found in Bridge (v02_n05).

In 1973, the expanding Resource Center materials were moved to larger quarters at 27 Eldridge Street. There, KW Chin and Yee Ling Poon, renamed the Resource Center as the New York Chinese Historical Society. It played an essential role in providing the groundwork for activities of the other areas of Basement, contributing to community activism. Many activities grew out of the Resource Center at 27 Eldridge Street with the printing of announcements, flyers, and leaflets calling for action. The accumulation of resources later became the foundation for the Museum of Chinese in America (MOCA).

In 1974, the U.S. Department of Health, Education and Welfare (HEW) funded and published the first official field study of Chinese, Japanese and Korean Americans12. Danny, responsible for the Chinese American section, was also appointed Director of this national Asian American study. The NY office for this project was housed at 32 East Broadway. Data from this study became the first official basis for action in Washington, DC, and for the first time, the concerns of Asian America existed on the federal government’s radar. Looking back, it was a milestone; for five years before, while African Americans were fighting for Black studies on campus, Asian American concerns were practically invisible.

Amerasia Creative Arts Collective: Making it All Possible

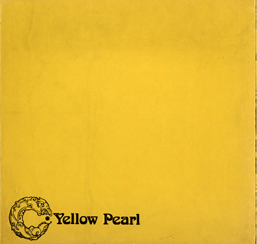

Danny studied Chinese painting and calligraphy when young. Then he studied Architecture and Urban Planning at Columbia University. Creativity and planning were at the core of his community activism. Aside from the three areas (Bridge Magazine, Asian American Resource Center, and Chinatown Community Planning Workshop), there was also the Amerasia Creative Artists group, the artistic arm and an artists collective of Basement Workshop. Most significant was the publication of Yellow Pearl in 1972, under the direction of Arlan Huang and Takashi Yanagida, it was an iconic collection of works by musicians, composers, literary, visual and graphic artists. In the form of a square yellow box consisting of fifty-four loose sheets of original art works, it has become a collection of historical value. Some prominent contributors included Nobuko Miyamoto, author of Not Yo’ Butterfly, and Larry Hama, known cartoonist and writer for G.I. Joe and others.

Many members of the Amerasia Creative Arts engaged the community with hand-on activities and classes in photography, video making, graphic arts, silk screening, printmaking, murals and public art, and performances in music, dance, theater, poetry recitals, and visual art exhibitions.

The Amerasia Creative Artists Collective, its robust energetic creativity contributed to all the programs at Basement. They provided the creative forces essential to action. The Arts served like glue that made it all possible.

Foundations and Futures

Towards the end of the 1970s, the Asian American Resource Center/New York Chinese Historical Society evolved into the New York Chinatown History Project, and spun off from Basement Workshop under the direction of Jack Tchen and Charlie Lai, and became the Chinatown History Museum. It was later renamed the Museum of Chinese in America, today a major Chinese American museum. Its history and origins trace back to Basement Workshop and its roots in the Chinatown community.

The Chinatown Community Planning Workshop, its many community classes in education, art, and services, gradually dissipated over time. Some members like Jeanie Chin13 and others continued their involvement in the development and progress of Chinatown. Others like Lydia Tom, KW Chin, Yee Ling Poon were founding members of the Asian Americans for Equality (AAFE), originally Asian Americans for Equal Employment. It is now a major housing organization providing low-income housing in New York City. In recent years, AAFE has resumed its connection to culture and the arts through the activities of the Asian American Arts Centre, and Think!Chinatown (T!C)14.

In 1981, AsianCineVision (ACV) took over the publication of Bridge until its last issue in 1985. ACV, a media organization that began as Chinese Cable TV (CCTV) by members and friends of Basement Workshop spearheaded by Peter Chow, was the pioneer in Asian American film festivals. It produced the first Asian American International Film Festival in 1978 at the Abrons Art Center, and continued its annual film festival in recent years at the Asia Society15. In the late 70s, it took over one of the Basement Workshop spaces at 32 East Broadway, after the conclusion of the field study, through the interim hands of filmmaker Tsui Hark.

In 1974, I took the dance component out of Basement Workshop and formed the Asian American Dance Theatre, performing and presenting traditional Asian and contemporary dance, and conducting classes for the community. In 1987 the name was changed to Asian American Arts Centre (AAAC)16, after visual arts and folk arts programs were initiated mounting exhibitions, events and talks, and developing an Asian American Artists Archive17. In recent years the AAAC has collaborated with Think!Chinatown on their exhibitions, and now has entrusted it with the stewardship of the Centre’s resources and art collection, soon to take shape as an Arts Research Center.

In the late ‘70s to mid ‘80s, what and who remained in Basement Workshop were members of the Amerasia Creative Artists Collective under the directorship of Fay Chiang (1952-2017). Programs in exhibitions and performances continued, promoting many artists and their works, until its closing in 1986.

Notes

1. The 1969 Chinatown Study Report can be seen at the Tamiment Library, New York University, under “Danny Yung Papers”. http://dlib.nyu.edu/findingaids/html/tamwag/tam_817/

2. See https://history.house.gov/Historical-Highlights/1951-2000/Immigration-and-Nationality-Act-of-1965/

3. Primary staff of the Chinatown Study Group includes Aline Chu, Corky Lee, Margaret Ma, Abraham Shen, Chung Tong Wu, Leo Yam, Ronald Young, Danny Yung, and Eleanor Yung. Others included Secondary Staff and Interviewers.

4. The Board of Directors of Basement Workshop included Chi Wing Ho, Peter Pan, Fred Wu. Danny Yung, and Eleanor Yung.

5. Some members of this group include John Young. C.T. Wu, Aline Chu, Wing Yee, T.C. Shen, T.K. Tong, N.T. Yung, C.L. Kuo. See “Danny Yung Papers at the Tamiment Library, New York University. http://dlib.nyu.edu/findingaids/html/tamwag/tam_817/

6. A total of 45 issues were published. They have been collected at major university libraries, e.g. New York University, Harvard University, Pittsburgh University.

7. Editorial Board of Bridge in the early years: Frank Ching, Margaret Loke, Richard Choy, Rockwell Chin, Peter Pan, Bill Wong, Odoric Wou, Bill Ling, David Oyama, Robin Wu, N.T. Yung, and others. For artistic contributions, please refer to Bridge. Collection can be seen at the New York University Tamiment Library and other major university libraries.

8. See Danny Yung Papers at the Tamiment Library, New York University. http://dlib.nyu.edu/findingaids/html/tamwag/tam_817/

9. CAPA’s APA Heritage Festival began in 1979 when President Jimmy Carter proclaimed APA Heritage Week the year prior. CAPA’s festival was held at Lincoln Center’s Damrosch Park, before it moved to Union Square. When the use of Union Square was denied, the festival moved around to various locations.

10. Confucius Plaza demonstrations brought together many Basement Workshop members including Takashi Yanagida, KW Chin among others.https://www.aafe.org/2018/05/44-years-ago-today-we-made-a-stand.html

11. The Chinatown Street Fair had much focus on Health, also known as the First Health Fair and the beginning of the Chinatown Health Clinic, which became the Charles B. Wang Community Health Center. See https://www.cbwchc.org/history.asp

12. Unfortunately, the HEW was abolished by Congress in 1979, and was split into the Department of Education, and the Department of Health and Human Services. The Asian American field study was buried amongst other documents of the agency. https://www.jfklibrary.org/asset-viewer/archives/usdhew.

13. Jeanie Chin, community activist since Basement Workshop, is founding member of the Civic Center Residents Coalition (CCRC) in activities against the changes in and around Chinatown by the NYC government post-9/11, which devastated the economy of Chinatown with lasting negative effects. She is point person against Mayor DeBlasio’s ongoing Mega Jail issue, and most recently fighting against club owners whose businesses would disrupt Chinatown’s residential area. For more information on CCRC, please see http:www.ccrcnyc.com. For Mega Jail issue, please see https://www.nubcnyc.com/.

14. For more information on the current art and cultural activities of Think!Chinatown, see https://www.thinkchinatown.org/.

15. For history of Asian CineVision and Basement Workshop, see https://www.asiancinevision.org/history/. Coordinators of the First film Festival in 1978 were Tom Tam, Danny Yung, Daryl Chin, Tikoy Aguiluz, Pat Yee and Fern Lee.

16. For information on Asian American Dance Theatre and the Asian American Arts Centre, see http://artspiral.org/.

17. For information on the Asian American Artists Archive, see http://artasiamerica.org/.

Author

Eleanor Yung was a co-founder of Basement Workshop, and co-founder and Artistic Director of the Asian American Dance Theatre (1974-1990), later renamed the Asian American Arts Centre (AAAC) in 1987.

Eleanor has a background in Sociology from the University of California, Berkeley, and studied Dance Education at the Teachers College, Columbia University. She has a Master of Science degree in Chinese Medicine, and practiced Acupuncture for twenty years before her retirement. She studied Taichi/Qigong with the late Master Ham King Koo, and taught at the Pacific College of Health and Science (formerly Oriental Medicine), the Metropolitan Museum of Art, The Clemente, and private lessons.

In 2008, Eleanor presented on, “Healing Aspect of Qi in Peking Opera,” at the NY APPAN First International Festival and Symposium: Meditation and Healing Dance & Music. Her essay, “Moving into Stillness,” appears in Chinese Women Traversing Diaspora (Routledge, 2013). She co-edited with Prof. Bell Yung, Uncle Ng Comes to America (MCCM Creations, HK, 2014), a multimedia publication on the narrative songs from southern China.

Eleanor’s oral history and dance works are archived at the Jerome Robbins Dance Division at The New York Public Library for the Performing Arts.

Back to Top Asian American Arts Centre

Asian American Arts Centre